President of European Central Bank Mario Draghi speaks during a news conference in Frankfurt, Germany, Thursday, Jan. 22, 2015, following a meeting of the ECB governing council. (AP Photo/Michael Probst)

President of European Central Bank Mario Draghi speaks during a news conference in Frankfurt, Germany, Thursday, Jan. 22, 2015, following a meeting of the ECB governing council. (AP Photo/Michael Probst)

“A sound banker, alas, is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.”

J.M. Keynes, The Consequences to the Banks of the Collapse of Money Values, 1931

As expected, the ECB has embraced Quantitative Easing (QE) in an effort to prevent outright deflation in the euro zone. The measures announced last week are bigger than most analysts expected, with the Bank committing to purchase €60 billion of bonds per month through 2016. More significantly, as Wolfgang Münchau has noted in the Financial Times, the ECB tied its purchases to its inflation target: the program could continue beyond its notional end date should inflation in the euro zone remain below the ECB's target. The adoption of this unconventional approach to central banking is, of course, welcome.

It also comes just in time. The election victory of the Greek Syriza party will likely introduce additional uncertainty into the euro zone as it seeks to relax the constraints of the Troika-led austerity program. In this environment, the risk is that deflation pushed on by lower oil prices takes hold and is incorporated into expectations in the same way that deflation became entrenched in Japan. In this uncertain environment, the impact of lower oil prices could be higher savings; not increased demand.

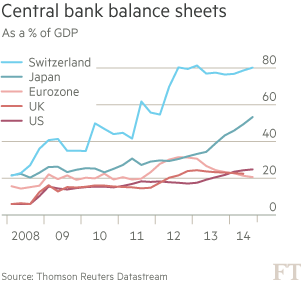

It is, arguably, three years too late however. The chart below (taken from Martin Wolf’s excellent discussion in the Financial Times) compares the balance sheets of major central banks since the onset of the global financial crisis and its subsequent morphing into the Lessor Depression. The ECB initially responded to the crisis with an injection of liquidity that expanded its balance sheet and again, more dramatically in late 2011 and early 2012 when the euro had a near-death experience. But unlike other central banks, it subsequently and many would argue, prematurely, consciously sought to unwind that expansion, fearing the inflationary consequences, or, possibly, German censure and the dreaded appellation of "unsound" central banking.

The real question, though, is whether the EC’s attempt to be ‘unconventional’ will succeed. (Although the ever-thoughtful Nick Rowe argues, here, that QE is really just Milton Friedman’s base control in practice and isn’t all that unconventional). Sadly, there is reason to believe that it will be less effective than it should be. As a friend observed before the ECB’s announcement: “the ECB is undoubtedly working hard to disappoint” [hat tip: RL]. Two factors figure prominently in this assessment:

- First, credibility. The QE program announced by the ECB last week doesn’t provide risk-sharing. Individual euro zone central banks will be responsible for losses on purchases of their respective bonds. But if the problem in the euro zone is the threat of protracted stagnation from a 1930s paradox of thrift, which stems from pervasive uncertainty, wouldn't it be a good idea for the central bank to mutualize risk to encourage private agents — firms and households — to invest, rather than save? Other national central banks, those that issue their own currencies, can do this via their balance sheets — in other words, by creating money. Individual central banks in the euro zone system can’t. As a result, the program may lack credibility in terms of its goal of jump-starting the economies of troubled euro zone partners.

- Second, effectiveness. The challenge in the euro zone is twofold: get households and firms to invest and get banks to lend. Even if the ECB program succeeds in the first of these objectives, it isn’t clear that it will induce banks to lend. This is important given the higher degree of financial intermediation in Europe, in contrast to the greater use of direct debt markets in the U.S. To some extent, euro zone banking is facing an adverse selection problem: the only borrowers seeking bank lending are those with higher expected default rates; banks can’t raise rates high enough to compensate for higher default rates because that would render projects unprofitable. It is a kind of Catch-22.

Despite these reservations, ECB QE is better late than never. And, as the old adage goes: “when the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.” Berlin has allowed Mario Draghi to take out a hammer. The question is whether he needs a sledgehammer.

0 comments:

Post a Comment